St Peter's Prep Schools ... The Difference Part 10

As parents we are proud of our children, try to protect them from disappointment and often demonstrate our love by expressing our admiration for them. Many parents routinely praise their offspring telling them how clever they are. For many of us, it’s an almost automatic reaction to say, “You’re so clever!“ when our children share a piece of work or something which they have accomplished.

The praise is well-intentioned and intended to boost the child’s self-confidence, but does it result in improved performance and achievement?

A decade and a half ago, we became aware of the work of psychologist, Carol Dweck. Her research strongly suggests that it may be the other way around. Praising children as ‘smart’ does not prevent them from under-performing. It might actually be causing it. A large group of fifth grade children in New York public schools were given a non-verbal IQ test consisting of a series of puzzles easy enough that all children would do fairly well. Each child was tested individually. Once the child finished the test, the researchers shared the child’s score and gave them a single line of praise. Randomly divided into groups, some were praised for their intelligence. They were told, ‘You must be smart at this’. Other students were praised for their effort: ‘You must have worked really hard’.

The pupils were then given a choice of test for the second round. One choice was a test that would be more difficult than the first, but the children were told that they would learn a lot from attempting the puzzles. The other choice was an easy test identical to the first. Of those praised for the effort, 90% chose the harder set of puzzles. Of those praised for their intelligence, a majority chose the easy test. The ‘smart’ kids took the cop-out.

‘When we praise children for their intelligence’, Dweck wrote in her study summary, ‘we tell them that this is the name of the game: Look smart, don’t risk making mistakes.’ And that’s exactly what the 5th-graders had done: they had avoided the risk of being embarrassed.

In a subsequent round, Dweck assigned a difficult test to all the 5th-graders with no choice, designed for children two years ahead of their grade level. Predictably, everyone failed. However, the group’s responded very differently. Those praised for their effort on the first test assumed that they simply hadn’t focused sufficiently on this test. ‘They got very involved, willing to try every solution to the problems,’ Dweck recalled. ‘Many of them remarked, unprovoked, “this is my favourite test.”‘ Those praised for their intelligence simply assumed that their failure was evidence that they weren’t really clever at all. ‘Just watching them, you could see the strain,’ said Dweck. ‘They were sweating and miserable.’

As her research progressed, Dweck discovered that those who believed that innate intelligence was the key to success, began to discount the importance of effort. Children reasoned that if they were intelligent, they wouldn’t need to put in any effort. Moreover, the effect of praise on performance held true for students of every socio-economic class.

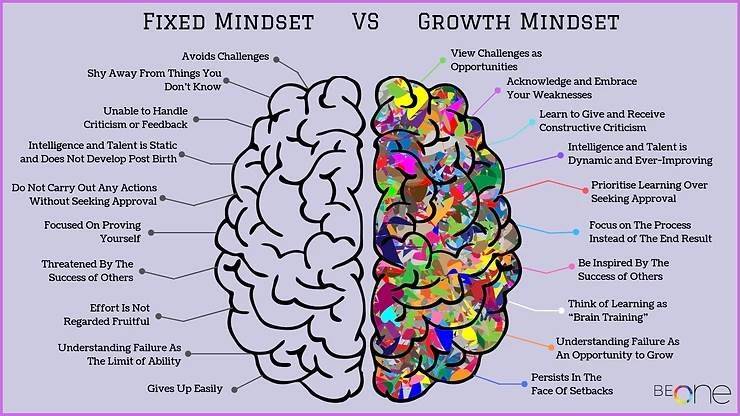

This led to the development of Dweck’s now widely known theory of growth and fixed mindsets. Essentially, fixed mindsets are characterised by belief that intelligence is innate and fixed and cannot be altered. Growth mindsets, however, see intelligence as something that can be developed with challenge and effort. Each view has a significant influence on our behaviour.

Carol S. Dweck, PhD

The study confirmed Dweck’s theory in a school of 350 students, diverse with respect to socio-economics, language, learning and special education status. By using a new common vocabulary aimed at praising effort, viewing intelligence as able to be developed and teaching the children how the brain works, significant improvements were recorded. Student-growth percentile in Maths MCAS scores rose dramatically in 2013 and were maintained in 2014. Typical growth in the state is 50 points but in Fiske (the study school), the student growth percentile was an average of 75.5 and the growth was maintained in 2014 across all 4th and 5th-grade students. In 2016, Fiske learned that they were one of thirty-nine schools being commended by the state for ‘high achievement, high progress or narrowing the proficiency gap’.

Studies in the 60s by psychologists such as Martin Seligman (the father of Positive Psychology) showed that in the face of repeated failure and without encouragement, people could become completely passive. This has become known as ‘learned helplessness’. The growth mindset theory and associated praise for effort and persistence overcomes such a condition. It is further encompassed in the quality ‘grit’, which St Peter’s encourages in all its pupils.

Conclusion

St Peter’s describes its methodology as ‘non-sectarian’. By this we mean that we are not wedded to a single methodology. The process of learning in humans is as complex as each individual and if we are to be successful in as many cases as possible, our methodology must reflect such diversity.

The learning process which we favour in our teachers and pupils, can best be summed up in the phrase: ‘relate…create…donate... ’. In relating, we confirm our understanding of the concept learnt. In creating, we apply this learning to other situations and circumstances. Once we have mastered the concept, we donate, by sharing our understanding with others.

Including so many diverse concepts in one’s teaching is far from easy and new teachers do not have an easy time of it when they join us. Thankfully, we have found that over the last decade, an increasing number of teachers are keen to join us and our ever-evolving quest to personalise learning for each individual child.